Social media isn’t driving the teenage “loneliness epidemic”

Mike Males, Principal Investigator, YouthFacts.org| January 2026

Americans of all ages suffer a “loneliness epidemic,” former Surgeon General Vivek Murthy announced in 2023, fostering health damage rivaling smoking “15 cigarettes a day.”

“In recent years, about one-in-two adults in America reported experiencing loneliness,” Murthy lamented. “Across many measures, Americans appear to be becoming less socially connected over time… Instead of coming together, we will further retreat to our corners—angry, sick, and alone.”

Well, that’s dark. We’d better remedy why we’re lonelier.

One big “socially isolating” factor Murthy cites, among several (after all, Robert Putnam’s [in]famous “Bowling Alone” essay first appeared in 1995, when primitive PC dial-up howled at 16 slow Mhz), is our devices: “social media, smartphones, virtual reality, remote work, artificial intelligence, and assistive technologies, to name just a few.”

Psychologist Jean Twenge argues that’s too wimpy: social media, particularly smartphones, are the villain. Severely truncating charts (i.e., chopping off the lower and upper 60 points on a scale of 100 to make trends look wildly more terrifying), she declares: “There’s something about being around another person – about touch, about eye contact, about laughter – that can’t be replaced by digital communication. The result is a generation of teens who are lonelier than ever before.” [Correction 1: online videochats do transmit eye contact and laughter; imagine the panic if they also transmitted “touch.”]

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt and his After Babel disciples agree. They insist their own generations that grew up in the 1970s and ‘80s before social media were happy, well-adjusted, and never lonely or anxious (“Phones?” one boasted. “No. We had each other.”) [Correction 2: teens of the 1950s-1990s logged plenty of phone time, along with hours of television and radio.]

Haidt sold at least one young core follower on his nostalgia of past adolescent bliss: “a time we never knew,” Freya India laments: now, her psychically tortured Generation Z suffers “anxiety (in) a phone-based world” of “loneliness, yes, but also the grief. The loss. The feeling of wanting to be free from the only world we’ve ever known.”

[This view has always puzzled me. If you feel so terribly oppressed by cellphones and social media, solutions abound: (a) don’t get a cellphone and online connection; (b) use the “off” button; and/or (c) click online tabs to block sites causing loneliness, grief, loss, anxiety, and entrapment (controls so easy even this 75-year-old regularly works them); then (d) go outside and frolic with friends in the soccer field sun and froyo fern patio. Look around. There’s no gun to your head! You don’t have to spend dark lonely months hunched over porn, Nazi, bullying, pro-ana, hate-your-body sites!]

Of course, there would be downsides, the same as if past generations had dumped their televisions, radios, Princess phones, arcade gaming, etc. (which likewise were lambasted as “addicting”). Still, a vocal fraction really seems to feel compelled to use technology to self-destruct.

Haidt also fails to mention that cities, malls, downtowns, etc., were so terrified of the teens of his day that hundreds of jurisdictions enacted juvenile bans and anti-cruising ordinances, culminating in the Clinton (yes, that Bill Clinton; ironic, huh?) administration’s mid-‘90s push for daytime/nighttime curfews so strict that teens would be allowed in public only a few hours most days of the year. And to stop the “touch” Twenge celebrates, thousands of schools, youth organizations, workplaces, etc., adopted “3-foot” personal separation rules.

All this leads to the final irony challenging the massive campaign berating us (and teenagers) that social media (especially smartphones) has horribly rewired today’s youth, the ultimate shocker…

TEENS’ LONELINESS HAS NOT RISEN OVER THE LAST HALF-CENTURY

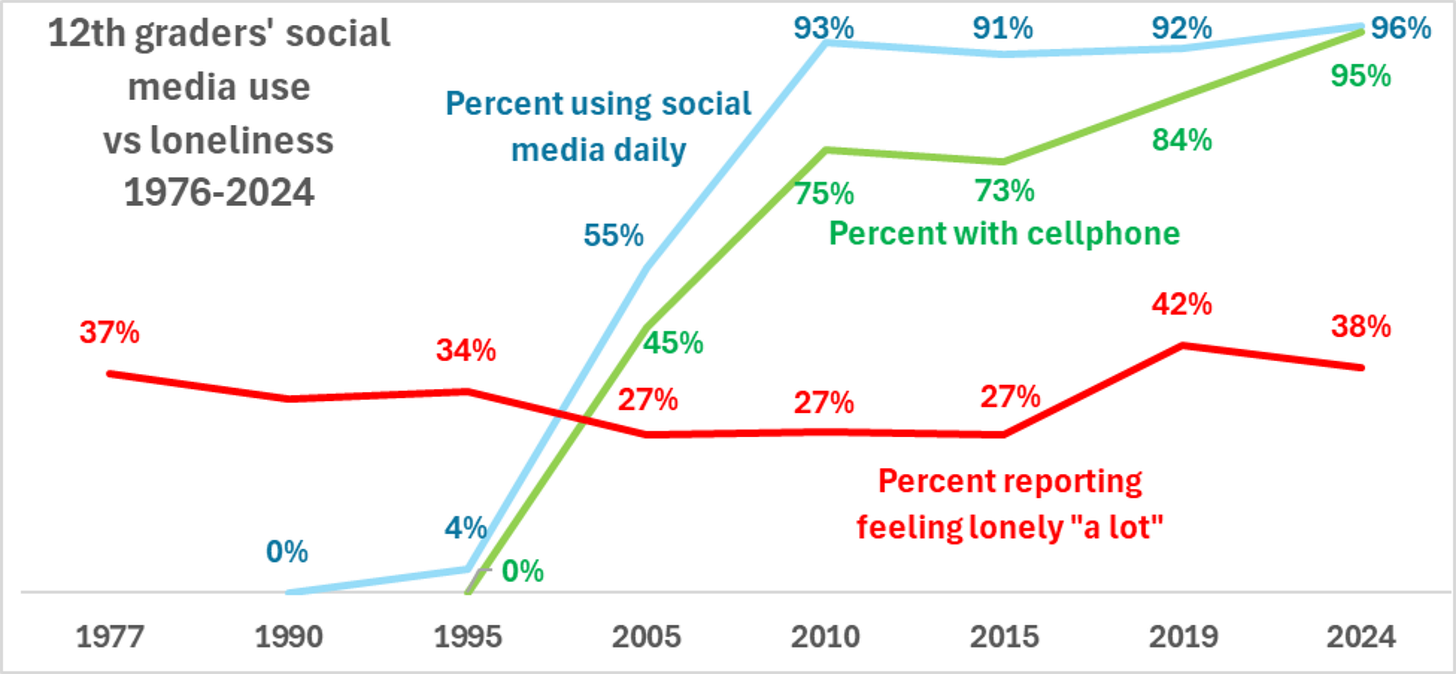

I graphed all 48 years of Monitoring the Future’s survey, the only one to ask the same question (“a lot of times I feel lonely”) of a consistent number (around 2,000) of high school seniors under the same selection process every year.

The change in high schoolers’ reporting loneliness – using a standard regression trendline to incorporate all years in the series instead of just cherry-picking the years that show what I want – is far below even tiny significance levels (d = 0.047, nothing), as the figures illustrate.

Sources: Monitoring the Future, 2025; Pew Research, 2007-2025.

Demolishing Haidt’s nostalgia, Twenge’s celebration, and India’s illusion of joyous warm-body togetherness prior to the social media/cellphone era, teens’ self-reported loneliness was high in the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s – long before social media and cellphones “destroyed adolescence.”

· When Haidt was 17 in 1977, 0% of youths had social media or cellphones, yet 37% of his teen peers reported to MTF feeling “lonely… a lot.”

· In 2024, 95% of teens use social media and cellphones, and 38% report loneliness to the same survey.

Not exactly the Four Horsemen. In fact, teen trends have been better on loneliness and many other indexes than those for both young adults and all adults.

How to rig your advocacy

Note how easily “trends” can be rigged to show whatever an advocate desires by cherry-picking which “before” and “after” years to compare – a disgraceful subterfuge routinely used in pop-academics’ and media discussions of social media:

· Want to show teenage loneliness has skyrocketed due to social media? Compare 2021 (46% reported being lonely) to 2007 (22%).

· Want to show teenage loneliness has plummeted due to social media? Compare 2007 (22%) to 1995 (36%).

Both comparisons are bogus. The first ignores that teens’ social media and cellphone use were already well entrenched by 2007, with only small increases afterward (see first figure). The second comparison tracks true growth in teens’ internet and cellphone use but then picks an arbitrary cutoff year (why 2007? Why not another year?)

Twenge’s exaggerated graphs fixated only on 2007-2019, a period when social media use stayed the same at over 90% and cellphone use rose only from 60% to 80%. By comparing two years in which a lot of teens used social media, Twenge actually shows social media is not the cause of the rise in loneliness she deplores.

Twenge obsesses over smartphones, whose popularity escalated in the post-2013 period. However, treating smartphones as somehow cataclysmic is also puzzling, since a smartphone is just a portable phone with internet capability, both of which teens already had. Further, teens’ loneliness had already increased from 22% in 2007 to 31% by the early 2010s before smartphones proliferated.

It would be interesting to study why (a) teens’ loneliness plunged in the early 2000s (my best guess is Millennials’ aforementioned froyo and soccer, replacing Gen-X mosh pits, mood rings, and pet rocks); and (b) both teens’ and adults’ loneliness rose in the 2010s before the COVID-19 pandemic, got worse during the pandemic, and now may be falling. Authorities’ blinding obsession with social media has quashed investigating more promising explanations for teens.

Perhaps teens’ definition of “lonely” have changed over time

How would a teenager of 1975 who talked on the phone for hours with friends, or a teen of today who videoed, gamed, messaged, and chatted with friends online, answer the open-ended question: “a lot of times, I feel lonely”? Has the rise of broader communications technologies in the internet era – sophisticated videochats and messaging supplanting the waxed string/tin cans, walkie-talkie, post-it note, and voice telephone of the past – changed the standards for describing oneself as “lonely”?

The next substack deals with nuances no one, amid the emotional panic over teens, social media, and mental health, seems interested in exploring.