The “teen suicides” and tragedies we don’t care about, Part 2

Mike Males, Principal Investigator, YouthFacts.org| September 2025

First: the never-mentioned context

Popular discussion of what we call “teenage suicide” and drug overdose is so horrendously messed up that we have to begin with basic context. Below is the CDC’s latest tabulation of suicides and overdose deaths by age group for 2024 and around one-fourth into 2025:

Source: CDC 2025. Overdoses refers to illicit, non-prescribed drugs.

The population sizes from 10-14 through 60-64 are similar, so these numbers indicate relative odds of suicide and overdose by age.

These are tragic numbers, much worse in the United States than in other nations. I would not argue for a second that 4,300 teen age 10-19 deaths from suicides and overdoses in approximately 15 months aren’t heartbreaking, both for the youths and those who cared about them.

Having said that, I will never understand the relentlessly destructive crusade by authorities and media to convince teenagers that suicide and drug abuse are normative to adolescence. In fact, teenagers are substantially less likely to commit suicide or overdose than adults are, a fact that should top all analyses.

In that respect, wouldn’t the 44,500 deaths from suicides and fatal overdoses among 40-49-year-olds – the average ages of teens’ parents, relatives, and nearby adults – also be terrible tragedies occurring at a level 10 times higher?

Deaths are just the iceberg tip of much larger abuse, mental health, addiction, absence, and violence issues that afflict troubled families in which millions of teenagers are growing up.

Have media-featured psychologists Jonathan Haidt, Jean Twenge, other popular commentators, political leaders, health professionals, and news reports shown any sensitivity or caring toward children and teens suffering parents’ and nearby adults’ suicide and drug abuse? Have any reported CDC survey findings that teens with troubled parents are much more likely to be troubled themselves? Somewhere between rarely and never.

Second: Teens have told us what drives suicide – we just don’t like their answers

The “teen suicide” discussion veers farther off the rails when we examine authorities’ rampant distortions of causal factors.

As I point out regularly (because no one else is), thousands of America’s teenagers told our largest, most definitive CDC adolescent health survey in no uncertain terms – twice – what the biggest factors contributing to their suicidal feelings and attempts are.

Teenagers’ answers on the massive 2021 and 2023 Youth Risk Behavior Surveys were so consistent and compelling that CDC analysts concluded in the in-house Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that three major childhood experiences – parents’ and household grownups’ “emotional abuse”, “physical abuse”, and “poor mental health” – were the driving factors in teenagers’ “suicide attempts (89.4%), seriously considering attempting suicide (85.4%), and prescription opioid misuse (84.3%).”

That is, for the factors we know about, nearly all teenage suicide and opiate abuse are associated with parents’ and household adults’ abuse, violence, and troubles. Virtually none are driven by social media.

So, how do authorities (mis)characterize these cold numbers?

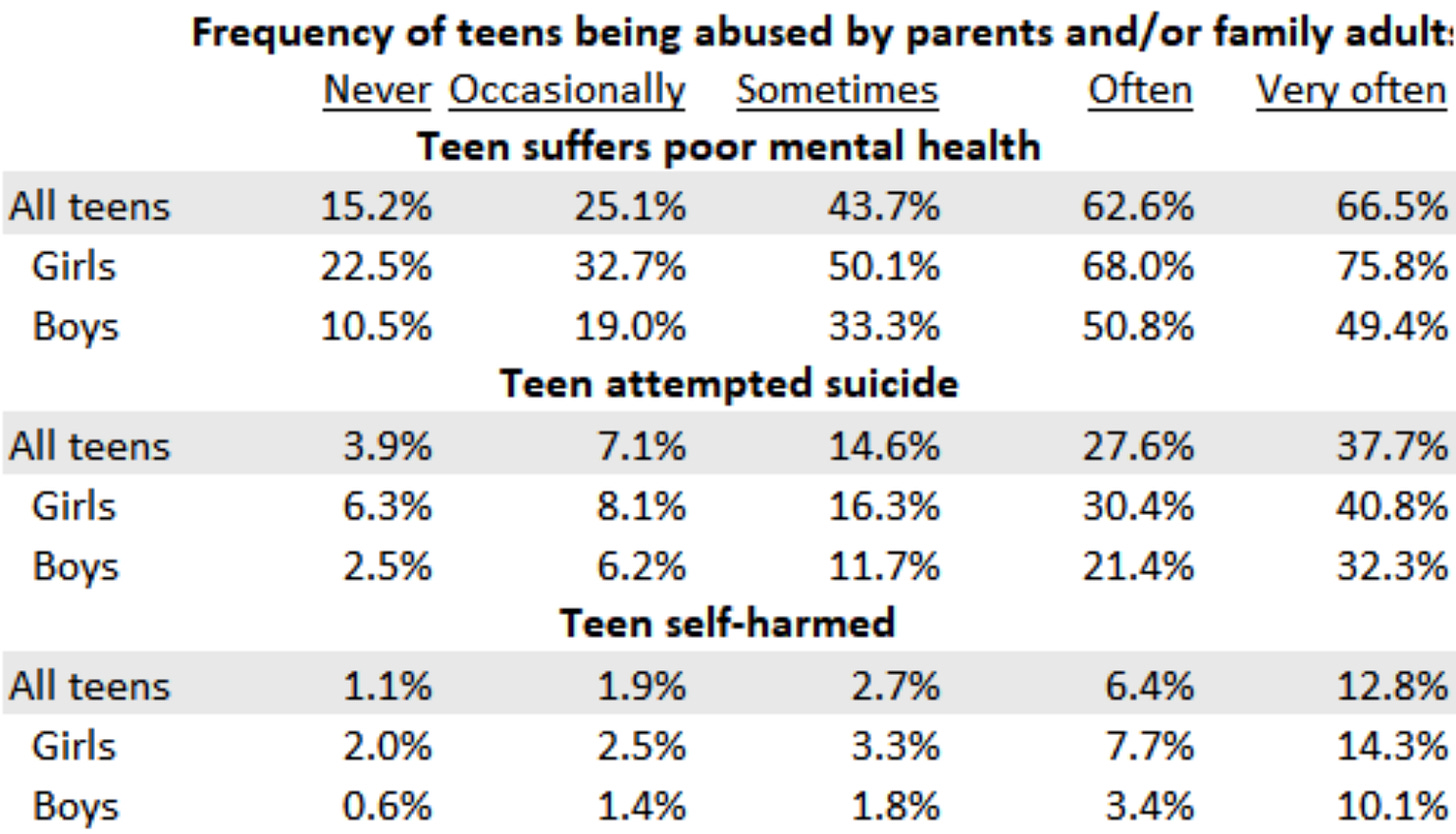

Again, let’s look at all the things public commentators and authorities leave out. The 2023 CDC survey finds, not shockingly, that teens who are abused by parents and household adults and have violent homes are far more likely to suffer poor mental health, make suicide attempts, and harm themselves.

Sources for tables: CDC, 2023.

No ambiguity there. Before skeptics shrug that teens always think their parents are crazy and abusive, consider that these are the same teens on the same survey whose answers authorities incessantly cite as proving the teenage “mental health crisis.”

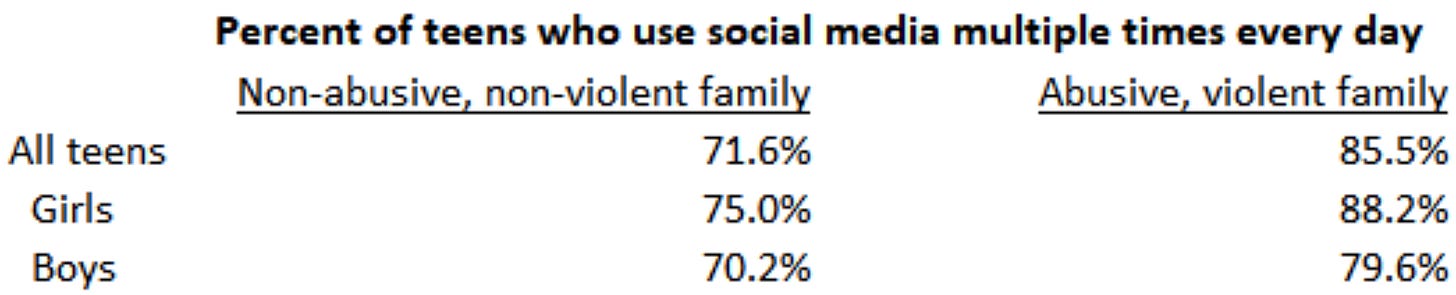

The CDC survey contains another never-mentioned bombshell: abused teens from abusive and violent families, particularly girls, use social media considerably more than teens from healthy families.

I wish I was making this next part up…

… because I can’t believe it, either. The pretzel-twisted consensus of leading officials and commentators from this compelling information seems to be:

· Teens are being truthful when they report their levels of depression and social media use; therefore, social media is causing their depression.

· However, those same exact teens on the same surveys are not being truthful when they report widespread abuse and violence by parents and household grownups; therefore, those survey answers can just be ignored.

Are top health, political, interest-group, and media-quotable authorities like Haidt and Twenge simply incompetent charlatans ignorant of the basic data shown on major health surveys, or dishonest distorters of crucial facts? We can certainly see the mentality that enables the Jeffrey Epstein perfidy.

Now it gets really bad

The CDC survey further shows that for abused teens, more social media use may be associated with less suicide and self harm.

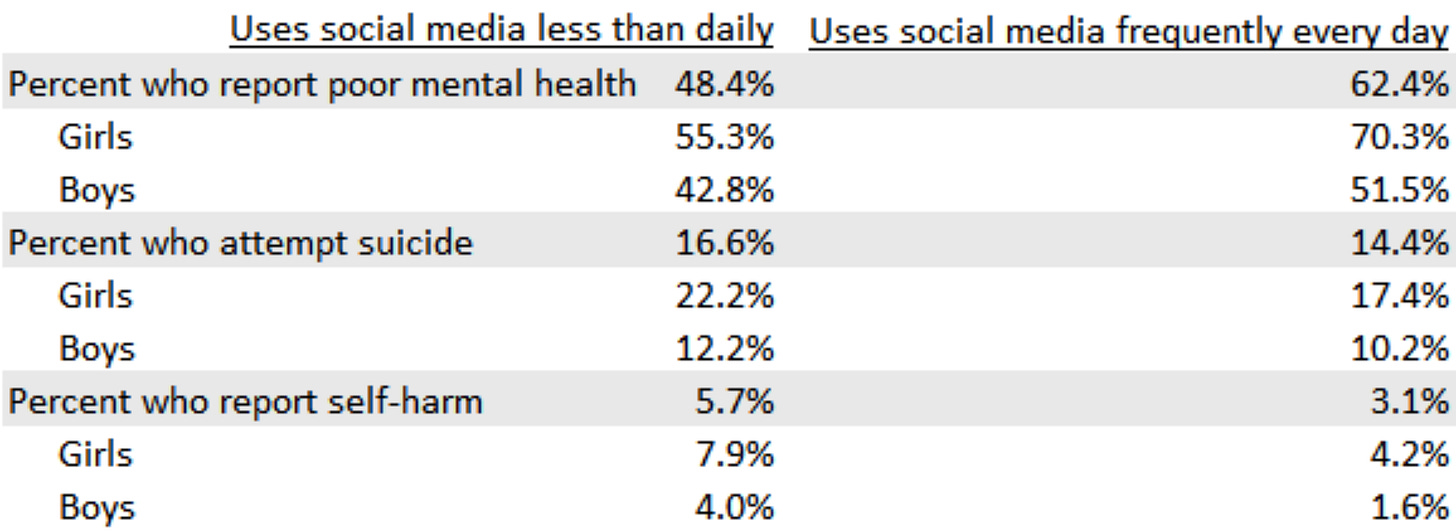

At first glance, this table would seem to validate concerns about social media. Looking only at the top three lines, abused teens who seldom use social media (less than daily) are considerably LESS likely to report frequently poor mental health (48.4%) than abused teens who use social media several times a day (62.4%).

Officials and popular commentators abruptly stop there: look, social media use and the cyberbullying it fosters makes teens more depressed. Don’t go any further!

Of course, that could be a reverse correlation: perhaps depression makes teens use social media more. What evidence suggests this is the more likely scenario?

Look at the next 6 lines. Abused teens who seldom use social media report being LESS depressed but MORE likely to attempt suicide (16.6%) and harm themselves (5.7%) than abused teens who use social media often every day (14.4% and 3.1%, respectively).

Presented more starkly and singling out teenage girls about whom authorities vent so much concern: 40% of abused girls who seldom use social media attempt suicide and 14% harm themselves, compared to 25% and 6%, respectively, of abused girls who use social media several times a day. Those are large differences reported by the most troubled population.

Talk about turning discussion on its head. We’re constantly hammered with zero-evidence emotionalities that more social media use drives more teens to suicide and self-harm when the best evidence indicates the opposite is more likely.

Again, though, we have to be wary of which way associations and correlations (especially ones that conveniently seem to validate our pet theories) really go. Perhaps teens who use social media more are simply more social, more inclined to seek help from others, in the first place. That would make social media less a savior of troubled teens and more just one of their self-help tools.

In any case, I can’t be the only one who looked at the CDC’s 2021 and 2023 surveys who noticed this obvious but fascinating pattern. So, wouldn’t you think these intriguing numbers from our largest, best surveys of teenagers would give authorities pause – at least provoke calls for further investigation – before rushing to demand wholesale bans and restrictions on teens’ cellphone and social media use?

If so, please send me your bank account passwords

I credit authorities, politicians, and media-beloved figures like psychologists Haidt and Twenge with scholarly awareness of teens’ complicated answers. It doesn’t take a post-doctorate stat-phenom to do cross-tabulation and regression analyses.

The CDC even tried to help them by issuing a colorful public report weakly blaming social media, cyberbullying, and peer bullying for teen troubles. Unfortunately for that cause, the report’s own numbers showed that even assuming social media and peer bullying are the only factors in teens’ lives, they are still associated with only trivial fractions of teens’ poor mental health and not at all with teens’ suicides… nothing like the 84%-89% associations the CDC found for parents’ abuses and afflictions.

Then, former Surgeon General Vivek Murtha issued a generally informative report on parents’ disturbingly widespread, rising mental health, drug/alcohol, and abusiveness that, well, just might, sort of, maybe, in the nicest wording possible, help explain teens’ mental health problems. That report, like the CDC’s survey analysis, was largely ignored by popular authorities and commentators.

Bummer

Even if science decidedly is not on their side, political leaders, pop-commentators, and media reporters can still invoke the old fallback: wildly hyping rare anecdotes in which a teen’s suicide or overdose possibly could be blamed on social media, peer bullying, and/or Artificial Intelligence (AI) and embellished as a “wake-up call!” revealing a heretofore hidden teen crisis.

The New York Times and dozens of popular media recently featured a teenager who committed suicide after receiving bad advice from an AI robot. The New Yorker ran a lengthy article on a teen who committed suicide after encountering bullying on social media, also a media theme when a case can be found.

Their stories deserve coverage (which they get) – and, even more, their full stories and context (which they never get).

The best evidence suggests small fractions of teens and adults have prior troubles that make them vulnerable to exacerbation by social media and AI technology, just as to family abuses, religion, harsh schooling, and other aspects of life. (For example, 82% of teens who tell CDC surveys they’ve been cyberbullied also report being emotionally abused by parents and household adults, yet another never-mentioned fact.)

If we only consider externally-driven destroyers of young lives, why aren’t stories like the mentally disturbed mother who hounded her severely troubled husband and young son into killing themselves – exactly what the NYT feature accused one teen’s AI robot of doing – as well as more parent-inflicted murders and suicides victimizing children featured just the week this is written, far more prevalent “wake-up calls”?

Because we care only about child and teen deaths that buttress profitable political agendas. “We are rushing into the same mistakes we made with social media,” declares a prominent commentator regarding AI and youth. I agree – for exactly the opposite reasons he cites.

We are allowing rampant misinformation and extremely rare, sensational cases (including those in which key facts have to be suppressed) to throttle discussion and policy that vitally affects children and teenagers. This isn’t caring about young people. It’s betrayal and cruelty.