Leftist commentators: Stop your dangerous demagoguery demonizing “young White men”

Mike Males, Principal Investigator, YouthFacts.org| October 2025

In the wake of the horrific assassination of rightist celebrity Charlie Kirk, I had hoped the liberal-Left would retain a healthy respect for facts, qualms about indulging in primitive culture-war scapegoating, and calming voices against right-wing lunacies.

Was I ever wrong

The derangements villainizing “young White men” as a generation vented by progressive podcasters I subscribe to and admired like Krystal Ball (Breaking Points), Kyle Kulinski (Secular Talk), Frances Fiorentini (Bitchuation Room), Jennifer Welch (I’ve Had It), et al, are as brainless and baseless as anything rightist-media dispense.

“Radicalized young men are combustible,” warns the leftist Daily Kos staff in an article thoroughly mischaracterizing the NBC Gen Z poll. “The manosphere and its influencers” are “feeding young men a steady diet of grievance,” creating a “toxic and dangerous” young-male culture of “online threats, mass shootings, and the growing overlap between misogynist and extremist communities.”

Check out my Daily Kos column re-analyzing the Gen Z “gender gap,” much more positive than typically depicted (readers of this substack can skip the last half of it!).

The Left’s crude culture-war scapegoating has not advanced a millimeter over Tipper Gore’s infamous 1980s’ crusade to vilify teenagers and metal, punk, and rap music.

Same old tune, 2025 verse: the 1980s teenage generation corrupted by Ozzy, gangsta, and video games, the armageddons of their day, now aging, insists that today’s apocalypse is young people corrupted by the “dark web.”

Imbecilic panics, shocking truths

America has a “problem” with “young White men,” Ball, Fiorentini, Owens, and leftist colleagues declare over and over since Kirk’s assassination.

No, America does not have a problem with young White men.

Krystal Ball, normally sane, hurls vilifications resembling Fox News’ at its rantiest. We don’t know the Kirk assassin’s motive, Ball admitted seconds before a 4 a.m.-vodka-rambling-mode of grotesque concoctions about his motive.

“We are witnessing the rise of the black-pill killers, predominantly young, White male misanthropes meming themselves into radicalism and violence,” Ball spat. “The all-consuming L-O-L L-O-L L-O-L of contemporary sad-young-man online culture, forum after forum dominated by an endless race to the bottom of nihilism and self-hatred” drives “a whole lot of young men. “The internet is acting as an accelerant” for shootings by “disconnecting us from real life, from real human beings,” a scary new scourge “unraveling” American society.

Aping MAGA illogic, Ball’s made-up speculations about the unknown motives of 5 shooters (who share little beyond young White male demographics) just happen, by merest coincidence, to fit her prejudices.

These speculations require ignoring a lot. Remember ultra-evil Adam Lanza, young White male slaughterer of 20 first-graders and 6 adults at Sandy Hook? Culture warriors broke eyeballs and minds ferreting dark influences. Bummer. Lanza’s online obsession turned out to be… Dance Dance Revolution.

Remember Charles Joseph Witman, the young White man who shot 42 people from the University of Texas tower in 1966, the worst school shooting ever? Eagle Scout, Marine, packing the Boy Scout Handbook. Be very afraid, alarumed singer-satirist Kinky Friedman, “there’s still a lot of Eagle Scouts around.”

Remember Patrick Purdy, young White male who committed California’s worst school shooting, gunning down 34 mostly Asian children at a Stockton’s Cleveland Elementary School in 1989? He might fit central-casting toxic; he raged against everything, long before the manosphere appeared. His was one of at least 5 big school shootings that year, back before Ball and others admit school shootings even happened.

Ball’s anti-factual, ahistorical rant is itself a sad descent into black-pill nihilism, in stark contrast to the healthy, compassionate messaging of young gamer men on the Kirk assassin’s own online Discord boards (see below).

Escapism – “it must be that horror comic, that tune, that TV show, that video game, that website” – goes on and on, newly perpetuated by the ever-self-destructive Left fabricating ever-new culture-war crap to demonize and demoralize its own young constituencies.

It’s all bullshit

Amid the lying, denial, and scapegoating on all sides, let us examine California, home to “a whole lot” of young White males, ground zero of online culture, and keeper of the country’s most complete statistics, the only ones to consistently record crime by detailed age, race, and ethnicity since 1975.

Homicide is by far the best-tabulated, then and now, combining police and medical examiner investigation. The numbers presented below surprise even me.

Ball says: “Rising nihilism” is driving “a whole lot of young men” to commit shootings. Bullshit.

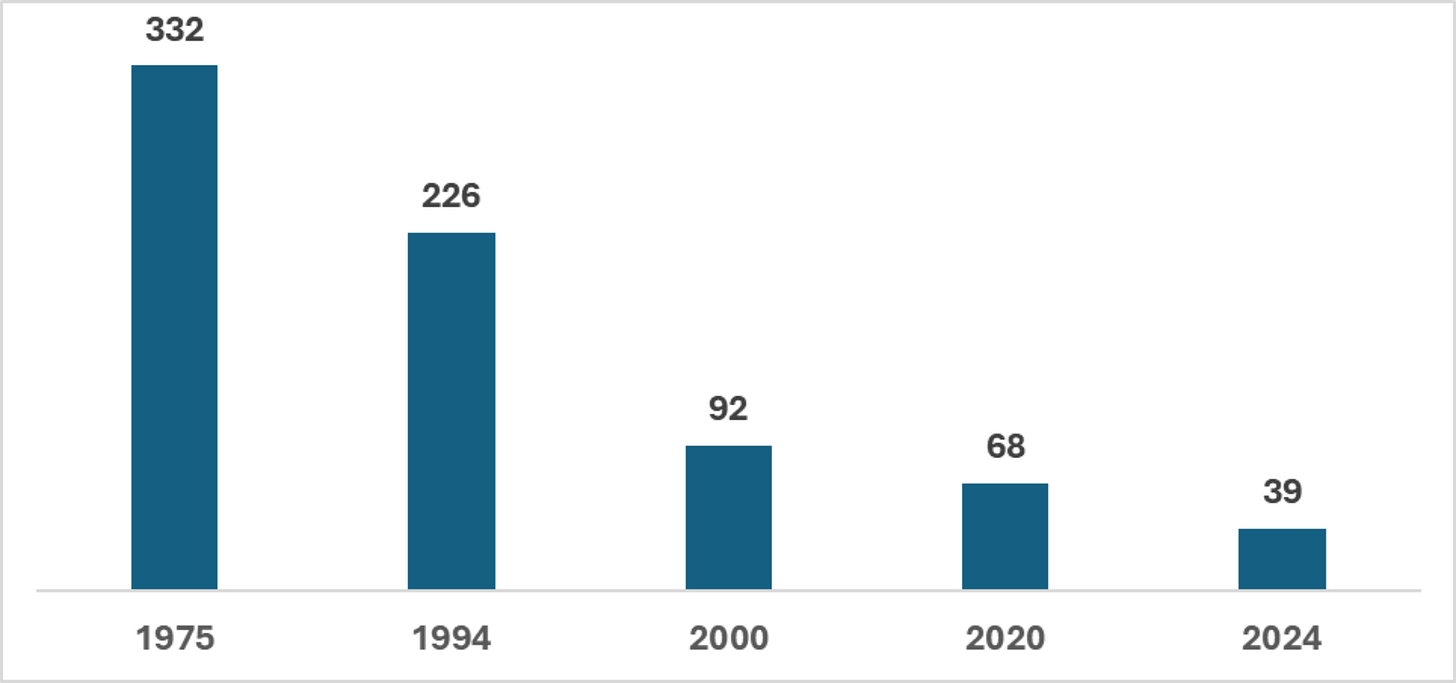

In 2024, a total of 39 of California’s 1 million young White men ages 10-24 murdered someone, just 3% of the state’s homicides. White men ages 25-34 and ages 35-44 each murdered more people, and White men ages 45-54 (the state’s richest demographic) murdered almost as many as all White male Californians under age 25 put together.

Ball says: “The internet is acting as an accelerant” for more murder. Utter bullshit.

Back in 2000, Krystal’s high school graduation year, California White males under age 25 murdered 92 people. In 1994, those halcyon days of warm human connection before the internet, California recorded 226 murders by White men under age 25 – nearly 6 times more. Back in Happy Days 1975, 332 – 8.5 times more.

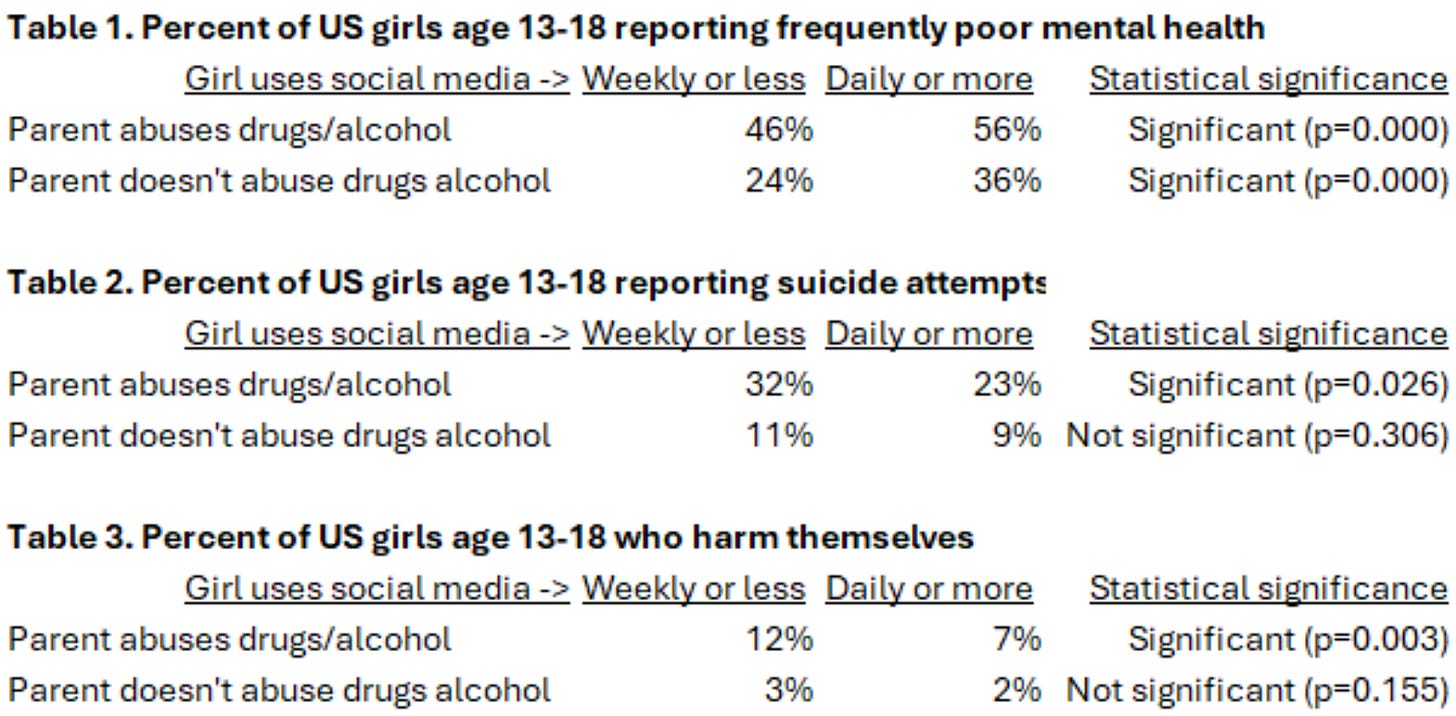

Number of homicides by California’s young White men under age 25, from the first year tabulated, 1975, to the most recent year, 2024

That is, California’s murder rate (adjusted for population changes) by young White men decades into the supposedly alienating, murder-accelerating online era is actually DOWN a staggering 75% to 80%. Other violent crimes have also fallen precipitously.

This is a shocking, revolutionary trend, paralleling the giant plunge in murder, violence, and crime by California’s increasingly diverse young people of all races over the last half-century.

Yet, the culture-war Left and Right STILL refuse to admit this fantastically positive trend happened alongside growing racial diversity. Their bleak, fictional agendas so desperately need young people always to be bad and getting worse that real trends are a threat that must be suppressed.

Are today’s far rarer Whiteboy murders different?

Culture warriors might respond that today’s young White male murders, though quantitatively far fewer, are qualitatively scarier and more nihilistic. Fair question, but… bullshit again.

It may be that more shootings take place at schools, though we don’t know. Small-casualty school shootings were considered local news prior to the Jonesboro and Columbine massacres in the late 1990s.

Young, White Manson Family’s creepy-crawlies who murdered celebrity “piggies” and dozens of others in the 1960s and ‘70s claimed inspiration from the Bible, Beatles lyrics, and acid. Young White teen Anthony Barbaro shot 14 people at Olean, NY, High School in 1974 in order to kill “himself.” Young White Barbara Ann Spencer shot 9 at San Diego’s Cleveland Elementary School in 1979 because “it was Monday.” You can pack a lot of scary nihilism into motives like that.

Well over 2,000 White males under age 25 were charged with murder in California alone during the 1970s. Maybe the much larger numbers of young White male murderers in the past were nobler, saner, warmer folks than today’s? Run that theory by survivors.

Glass houses

Ball and progressive colleagues, after banging on endlessly about nihilistic chats and toxic manospheres, sometimes tack on a laundry-list of other ills such as gun availability, lack of mental health care, income inequality, COVID isolation, etc.

Even that quick list leaves out the biggest factor – the deteriorating behaviors of Ball’s and colleagues’ own parent-age generation.

Most of the commentators on progressive shows are members of a parent generation that murders at least 900 children every year in substantiated domestic violence – 30 times more children than are murdered at school even in bad years.

Ball is 43. Co-host Saager Enjeti, who also demagogues on “juvenile crime,” is 33. Fiorentini is 38. Kulinski is 37. Do the parent podcasters take the same collective responsibility for their age-mates’ much larger body count that they would impose on young people?

Hell, no. Even when fixating on mass and school shootings, which account for fewer than 1% of American homicides, commentators lie like last year’s bathmat.

The FBI’s latest, 2024 report on mass shootings shows, “the 25-34 age category had the most shooters” and “the shooters’ average age was 39 years old.” It’s not just individual homicides; more children are murdered in mass shootings at home than at school, JAMA Pediatrics reports.

More murders, more mass shootings, more violence… what dark cultures are over-25 generations consuming?

Despite the fact that liberal-Left podcasters’ over-25 generation is better off economically, with higher incomes and lower poverty rates that traditionally protect against risks, America’s 25-44-year-olds are perpetrating more crime, more violence, more suicide, more drug and alcohol overdose, more abusive behaviors, more bullyings, beatings, and murders victimizing children and youths, more mass shootings, and more crazed politics wrecking the futures of young people and the planet, both in gross numbers and per-capita rates compared to younger ages.

Today’s parent generation violently abuses one-third of its kids, emotionally abuses 60%, and subjects one-third to 40% to parents’ and family grownups’ drug/alcohol abuse, criminality, and severe mental health problems in their homes, the 2023 Centers for Disease Control survey reports. Today’s 25-44-year-olds are the first reliably-documented parent generation that is more likely than their teenagers to be arrested, including for violent crimes, public disorder, and even dumbass stuff we used to think only teenagers committed like vandalism, arson, and shoplifting.

Gen Z’s one negative statistic is that they’re more anxious and depressed. They’d be crazy if they weren’t.

Am I being reverse ageist?

Not fair, the average parent might react, we don’t commit crimes, overdose, or (god forbid) abuse or murder our kids. We’re lovely individuals, stellar moms and dads. We don’t hate our teenagers.

True, and that’s the double standard. We grownups demand to be judged as individuals, not as a faceless mass collectively guilty for all the crimes and shootings our agemates do.

Remember the raging that elder America had gone off the rails after that 64-year-old shot more people in Las Vegas in 15 minutes than are shot in ALL 130,000 American schools in 4 years? Oh, wait, there wasn’t any anti-elder raging. Old people have power. Older people vote.

Then, we turn around and deny that same individuality to “young men,” glazing the demographic scapegoat as “young White men” to dodge media euphemists’ use of “young men” and “youth violence” as codewords for “Black.”

What monsters

Amid the crapshow, reporter Ken Klippenstein took a radical step: actually interviewing the assassin’s closest Discord platform friends and obtaining their messaging. What a letdown. Klippenstein found nothing that supported vivid official/media fantasies of godless dark-web manospheric Nihilist Violent Extremist cells slobbering for mayhem.

“The picture that emerges bears little resemblance to the media version,” Klippenstein wrote. He found friendly gamers chatting in Discord forums who were horrified to learn of one of their friend’s murderous deed. Close friends described the shooter as quiet, well-liked, and apolitical. “The friend group who he interacted with on Discord, far from some kind of militia camp or Antifa bunker it’s been portrayed as, represented a range of different political views but mostly talked video games.” Cats were a frequent topic as well.

One of the killer’s online friends led a prayer others joined for Kirk and his family. Far from inflaming murderous conspiracies, the young men online seem deserving of all sides’ praise for reactions far healthier than those of dominant Right-Left conspiratorial foamers.

Enough

To sum up what should be obvious ethics: no collective guilt, no mass generalizations from rare events, no wildly prejudicial assumptions and stereotyping, no scapegoating.

It’s not okay to vilify young people because they have no means of organized response to defamation. Indignance at cultural outrages – yes, there’s bad stuff online, and also in churches, schools, locker rooms, Sunday night poker, on and on – does not justify substituting grossly fabricated assumptions for diligent research.

Krystal Ball, Daily Kos, and other who demagogue this volatile issue owe young men an abject apology.