Are U.S. schools dangerous places for gun violence?

By Mike A. Males, YouthFacts

April 24, 2023

A number of mass shootings have made the United States’ K-12 schools the focus of the gun safety debate and often extreme “solutions” to prevent them. However, a straightforward risk analysis shows the chances of being shot or suffering any kind of gun incident, fatal, injurious, or otherwise, is far lower in a K-12 school per hour spent there than elsewhere in American society. Even assuming maximum risk, an American student or adult staff would have to attend school daily for 397 years to suffer even odds of a gun incident of any kind, and for over 200,000 years to risk personal gun injury or fatality, about the same risk as a resident of Germany. An American child is many times more likely to be murdered by guns at home than at school. Drastic measures such as arming school personnel and/or mass screenings of students using dubious psychometric instruments are unwarranted. Gun safety policy should be based on reasoned assessments of dangers, not emotional campaigns.

Highly publicized mass shootings have made K-12 schools in the United States the focus of intensive fear, media coverage, and proposed solutions to the country’s epidemic of gun violence. Commentators regularly state that students should be “terrified” of being shot in schools, parents should be afraid to send their children to school, and extreme measures including mass psychiatric screenings of students and hundreds of thousands of armed guards in schools at annual costs of tens of billions of dollars should be implemented.

Fears of school shootings began in the late 1990s and escalated with the 1999 mass shooting at Columbine High School. The numbers of school shootings, along with mass shootings in general, have risen beginning in 2017. From 2018 through 2021, 144 people died in 602 school shootings, broadly defined as all fatal, injury, non-injury, stray-bullet, and gun brandishing cases in or around a K-12 school (Reidman, 2022). This study covers July 1, 2021, through June 30, 2022, a period which includes the Uvalde, Texas, mass school shooting, which accounted for 43% of the student school shooting deaths during the period and which boosted the death toll from school shootings substantially above those of previous years. Despite these horrific occurrences, the hypothesis of this analysis is that schools will prove safer from gun violence than other areas of American society.

Should children be “terrified to go to school”?

The widespread assumption that schools are dangerous places for gun violence suggests that to be persuasive, this analysis must deliberately adopt assumptions and measures that make the above hypothesis affirming relative school safety harder to prove. To that end, this analysis incorporates the broadest possible definition of a school shooting, the maximum enumeration of school shooting victimizations, and the one-year period during which the most shootings occurred – all pessimistic, counter-hypothesis assumptions – to calculate the risks of experiencing a shooting in a school per hour spent there.

How much time do Americans spend in K-12 schools? In 2022, the National Center for Education Statistics (2022, 2022a) estimated that 55.7 million students, 3.6 million faculty, and three million additional staff were enrolled or employed in 130,930 public and private K-12 schools. At an average daily attendance of 93.2%, 55.3 million persons would be present in K-12 schools for an average of 6.64 hours per day for 167 days per year.

School shootings are defined by the School Shooting Safety Compendium compiled from 25 sources by the Department of Homeland Security’s Center for Homeland Defense and Security (CHDS, 2022) as including “each and every instance a gun is brandished, is fired, or a bullet hits

K-12 school property for any reason, regardless of the number of victims, time, day of the week.” All shootings, including suicides and those of unknown intent, are included regardless of whether they occurred during regular school hours or involved school-related participants. This analysis counts all school shootings in the SSSC database from July 1, 2021, through June 30, 2022, victimizing persons under age 19, including all those whose ages are listed simply as “child” or “teen”, as student victims whether they were enrolled in school or not. The few victims of unknown age are apportioned to students the same as those of known age.

Corresponding national firearms death totals used to estimate dangers elsewhere in American society are tabulated by the Centers for Disease Control (2022) for calendar year 2021. Ideally, comparison of school shootings would be to the exact same time period, but 2021-2022 national figures are not yet available. Further, in keeping with the study goal of “stacking the deck” to maximize the impact of school shootings, 2021-2022 is chosen for school shootings to include the Uvalde mass shooting to maximize school victimization numbers, while 2021 is chosen for the national comparison even though preliminary projections indicate 2021-2022 gun mortality numbers will be higher. The analysis thus uses the most recent data available at this writing.

Based on these assumptions, Americans spent approximately 69.4 billion person-hours in K-12 schools in 2020-21. On a full-time annualized basis, then, American K-12 schools amount to a “nation” of 7.9 million people, between the national populations of Denmark (which suffered 84 shooting deaths in the most recent year) and Belgium (143). Assuming that the 72 total annual fatal shootings and 258 shooting injuries (including minor injuries) in 329 school firearms incidents in 2021-2022 represent the new normal, there would be 1.02 fatal and 3.75 injury shooting casualties per billion school person-hours. Focusing only on students, persons ages 5 17 spent 62 billion person-hours and, under maximized assumptions, suffered 44 fatalities and 175 injuries from shootings in schools in 2020-21. How does American school gun safety compare to other venues?

=Based on the most pessimistic assumptions from the highest year for school shootings and a broad definition that includes shootings originating off-campus and outside of school hours, a student or adult school employee would have to attend school every school day for 397 years to experience even odds of having a firearms incident of any kind – fatal, injurious, missed-firing, stray-bullet, or gun-brandishing – occur at their school. A student would have to attend school every school day (allowing for average daily attendance) for 208,000 years to risk being personally killed or injured in a shooting, and for nearly 1.2 million years to suffer even odds of being killed in a school shooting.

For all ages, 2.4% of total time is spent in a K-12 school, and 0.3% of all gun homicides take place in a school. Students ages 5-17 spend 12.2% of their total hours in school each year and suffer 3.0% of their gun homicides and 1.8% of their total gun deaths in or around the country’s K-12 schools.

These odds make schools among the safest places in the United States from shootings, fatal or otherwise. Per billion person-hours spent elsewhere in society other than at a K-12 school, the average American of all ages is 16.3 times more likely (including 7.3 times for homicides and 211 times more for suicides), and the average 5-to-17-year-old is 6.7 times more likely (including 4.2 times for homicides and 50.7 times for suicides), to suffer a fatal shooting.

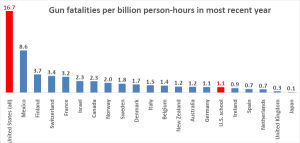

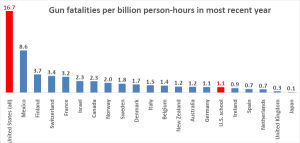

However, the United States does not set a high bar for gun safety. How do American schools compare to the greater safety from guns found in other Western nations? Figure 1 compares firearms death tolls per billion person-hours for the United States and U.S. schools to those of Mexico and 18 affluent Western countries (World Population Review, 2020). While the United States ranks the worst by far for shooting deaths, its schools rank favorably with other Western countries as a whole. A person walking the hallways or campuses of an American school risks about the same odds of being shot as a person in Germany.

This risk calculation in no way diminishes the disturbing reality of school shootings or shootings elsewhere, mass and otherwise. Incomplete tabulations indicate that while U.S. schools are much safer from gun violence than elsewhere in American society, U.S. schools are much less safe from gunfire than schools in other Western countries. “The notion that school shootings are a uniquely American crisis" is difficult to dispute given their alarming frequency in the U.S. compared to the rest of the industrialized world,” World Population Review’s analysis concludes. Of 330 known school shootings worldwide in 2022, 288, or 87%, occurred in the United States (World Population Review, 2022), which has around 4% of the world’s K-12 students. The extent to which nations other than the United States keep complete records of shootings in schools is not known, perhaps because such shootings are rare in other countries. The paradox that American K-12 students are much safer from gunfire in schools than elsewhere in American society and at the same time much more in danger of shootings than students in other Western nations’ schools is the kind of innovative information that can yield powerful policy insights.

Conclusion

Americans who fear gun violence should be more frightened when a child or youth leaves a school than when they enter one. As other Western countries have shown, the shooting death of anyone, anywhere is a preventable tragedy, but we attach a special sadness to the death of a young person because of the greater loss of years and potential. It is because the shooting of a young person is a tragedy – especially in the quantity child gun victimizations occur in the United States – that the most accurate information and carefully designed policies must be applied to preventing them.

The unreasoning panic over school shootings to the exclusion of broader gun violence concerns damages effective policy and endangers young people. Gun-rights activists’ campaign to arm school officers and teachers is particularly alarming. If just a fraction of 1% of the hundreds of thousands of personnel armed with assault weapons who would be installed in schools at costs of tens of billions of dollars annually under gun-rights proposals turn out to be mentally or criminally disturbed, children would be in far more danger of being shot in school than they are now. Indeed, unwarranted shootings of other officers, adults, students, and themselves by armed school officers already have occurred. That policy recommendations like these are gaining traction results from vast overestimates of the dangers children and youth face in schools and misallocation of limited resources available to ameliorate gun violence.

The failure to set rational priorities means more people, including young people, will be shot.

The small fraction shot in mass school shootings by young peers are granted such high-priority

status for grief and policy remediation that the vast majority of child victims who are shot at

home by grownups are treated as unimportant and unworthy of mention. The FBI’s tabulation of age of shooter by age of victim shows more than three-fourths gun murder victims under age 12 were shot by adults ages 25 and older; just 5% were shot by peers under age 18, fewer than are shot by grownups age 50 and older (OJJDP, 2022).

Why are schools relatively safe? That, even in a country with staggering gun fatality, American schools suffer gun violence levels comparable to those found in Germany, Australia, New Zealand, and Belgium appears to relate to one commonality: like other Western nations, and unlike other American venues, American schools are almost all gun-free. Straightforward mathematical analyses of state gun-law strictness, proportions of households with guns, poverty levels, and gun death rates by type consistently show that gun proliferation and poverty levels are the major predictors of firearms homicide and overall gun death rates. Domestic violence inflicts a much higher gun violence toll on children than shootings in schools.

The clear desire of political, interest-group, and major-media commentators and authorities to avoid the uncomfortable implications of these realities shows the gun debate is more about advancing partisan agendas than protecting young people. While it is unarguably true that school shootings are tragic and deserve outrage, the exclusionary fixation on them has produced extremist “remedies” that would increase, not decrease, danger to students. We do not need hundreds of thousands of assault-weapon armed vigilantes roaming school hallways and campuses. We do not need mass screenings of tens of millions of students using dubious psychometric scorings (see Ferguson, Coulson, Barnett, 2013, 2011). It is long past time to move into a realistic era of reasoned assessments of real gun violence dangers and scientific responses.

References

Center for Homeland Defense and Security (2022). Data map for shootings at K-12 schools.

https://www.chds.us/ssdb/data-map/

Centers for Disease Control WONDER (2022). Provisional mortality statistics, 2018 through last

month. https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10-provisional.html

Education Week (2022), Education Statistics: Facts About American Schools.

https://www.edweek.org/leadership/education-statistics-facts-about-american-schools/2019/01#:~:text=How%20many%20schools%20are%20there,for%20Education%20Stati

stics%20(NCES).

Ferguson, C.J., Coulson, M., Barnett, J. (2013, 2011). Psychological profiles of school shooters:

Positive directions and one big wrong turn. Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations, 11:1–17. At:

https://www.christopherjferguson.com/ProfilesSS.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics (2022). Digest of Education Statistics, Tables 201.10,

208-20, 213.10. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_208.20.asp?current=yes,

https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_213.10.asp?current=yes,

https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d20/tables/dt20_201.10.asp?current=yes

National Center for Education Statistics (2022a). Schools and staffing survey.

https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/sass/tables/sass0708_035_s1s.asp

Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) (2022). Easy access to the Supplementary Homicide Reports: 1980-2020.

https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezashr/asp/vic_selection.asp

Reidman, D. (2022). Naval Postgraduate Center for Homeland Defense and Security. K-12

school shooting database. https://k12ssdb.org/all-shootings

World Population Review (2022). Gun deaths by country, 2022.

https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/gun-deaths-by-country. School shootings

by country, 2022. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/school-shootings-by-

country. Total population by country, 2022. https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries

published a provocative new study, Lives in Limbo: Undocumented and Coming of Age in America (University of California Press, 2016). Similar to the fears illustrated by the civil authorities referred to above, Gonzales explores the consequences of a society entangled in fear: this time it’s fear of immigrants. Another judgment follows: the destruction of the life chances of the 2.1 million youth permanently trapped, “undocumented,” by careening public policy.

published a provocative new study, Lives in Limbo: Undocumented and Coming of Age in America (University of California Press, 2016). Similar to the fears illustrated by the civil authorities referred to above, Gonzales explores the consequences of a society entangled in fear: this time it’s fear of immigrants. Another judgment follows: the destruction of the life chances of the 2.1 million youth permanently trapped, “undocumented,” by careening public policy.